Part I - Smart contracts as the natural evolution of analog contracts: The case for legal equivalence between offchain companies and blockchain-native organizations

In this second post, we examine how onchain companies can achieve legal equivalence with offchain registered ones.

Companies are an invention, and as inventions go, they arguably rank equally with the printing press, the shipping container, and the micro-processor in how they impacted human progress.

The key breakthrough lies in the acceptance of the legal fiction that a company has its own legal persona, separate from who owns it.

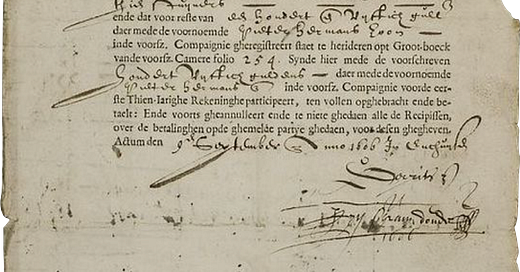

Back in the Low Countries in the early 17th Century, the joint-stock company then contractually limited the liability of its owners to the capital they contributed.

This resulted in a power-law proliferation of risk taking and private entrepreneurship which has continued up to the present day.

Companies remain largely a matter of private contract law

Though the State (as it did with currencies which were once issued privately too) eventually monopolized the chartering of companies, most matters related to the relationship between a company’s owners and its managers and how a company is generally governed remain a matter if private contract law.

Private companies in particular remain in essence a bundle of private agreements between various stakeholders and are arguably one of the few playgrounds of free enterprise left.

Predictably, lawyers became the self-appointed guardians of the key agreements governing the relationship between company owners, their managers and the outside world, building upon caselaw to crystalize a body of law referred to as corporate law.

This has resulted in a more or stable set of constitutional documents across most commonly used company structures, such as the Operating Agreement for the U.S. Limited Liability Company, the Bylaws of a U.S. C-Corp, and the Memorandum and Articles for most non-U.S. limited companies.

Legal parochialism

When contracts in legal prose execute, it creates a binding relationship between the signing parties.

However, legal agreements by their nature cannot self-enforce: Whilst lawyers go to great lengths to define what constitutes a breach of contract and the consequences of such breach, they cannot prevent a breach in itself.

The above hints at a key vulnerability of analog legal arrangements: as in Gödel’s completeness theorem, analog legal clauses - no matter how neatly worded - ultimately rest on a principle of trust which exists outside of the narrow contractual context. Simply put: A legal agreement is always to some extent a leap of faith.

Such leap of faith was easy to take when companies were setup from a coffeehouse in Amsterdam, where capital was pooled by confraters whose daughters had married each others sons, and the stock exchange was a club of cigar-smoking males agreeing a fair price over a jenever.

Legal parochialism still characterizes most of how companies are formed, funded and governed today, but is patently inadequate for the digital economy where teams are distributed, stakeholders are contributors, and governance is independent of physical location.

What’s needed is a new entity for the new economy.

We had to wait for blockchains

The key breakthrough from smart contracts on distributed computing is not only that they create binding legal agreements (because you agreeing to Apple’s new T&Cs served up via a centralized server also creates a binding legal agreement), they also make trustless contracting possible by embedding the contract terms in self-enforcing code which cannot be censored or changed by any of the contracting parties (or can only be changed by following pre-agreed protocols part of the code).

Smart contracts are therefore deployed rather than executed, and thanks to this self-executing nature of smart contract, analog agreements when transposed into computer code can be made self-policing. In that sense, smart contracts are legally Turing complete.

Applied to a company’s constitutional documents and its governance bylaws, most of the operational legal clauses break down into IF > THEN conditionality.

For instance:

A typical clause in a shareholder agreement may specify that IF any individual spend by management exceeds say US$100,000, THEN approval of a shareholders is required.

Analog legal prose won’t prevent a rogue manager from buying a $110k diamond necklace with the company’s card. The only recourse is suing for restitution after the deed is done.

In a digital context however, the company’s treasury is held in a wallet programmed to ping for a shareholder’s cryptographic signature IF any individual payment out of the wallet exceeds $100k. Only THEN can the transaction happen.

The legal fiction of a company as a bundle (occasionally a spaghetti!) of legal agreements, combined with the IF > WHEN logic of most of a company’s constitutional agreements and bylaws, make it possible to systemically replace the analog mechanisms of checks and balances between the parties into computer code.

If some of this code execution depends on external events, oracles can be used.

As indicated in previous posts, nowhere is this more true than in Venture Capital deals: while smart contracts won’t (and were never meant to) replace human negotiation and consensus building, it is our believe that the key clauses related to the economics and control elements of an investment can be embedded in smart contracts.

Programmable companies

What emerges is a company in which all participants, rather than holding dumb tokens that simply represent their percentage ownership, own programmable shares that reflect each participant’s role and privileges in the organization. The system itself can then check if the conditions are met to see certain things happen.

For instance, certain “reserved matters” which typically require the vote of a “qualifying shareholder” would simply not be adopted without such shareholder’s cryptographic signature.

The same goes for rights of first refusal clauses, anti-dilution adjustments (which would be fully automated by the smart contract minting more ownership tokens), automatic conversion, etc.

More generally, the mechanics of the governance of the future company and its business logic, including the myriad humdrum corporate secretarial actions, will likely be automated via smart contracts, in combination with AI.

Other legal constructs such as trusts and investment funds too, when blockchainified, would see a lot of the maddening anachronisms that currently plague their running taken out of the equation.

II. The legal equivalence of blockchain-native companies

Programmable companies are exciting. However if all we do is transpose existing company forms to a new technology layer, we are doing nothing to broaden ownership and democratize participation.

In what follows, we make a case for a new, digital entity for the digital economy, and further argue that the recognition of such entity is attainable by relying on accepted principles of international private law.

Doubts about DAOs

Much has been written about what has generally been referred to as Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (“DAOs”, originally called Decentralized Autonomous Corporation or “DACs” by Nick Szabo who in our knowledge used the term for the first time in 1994).1

In their purest form, DAOs aren’t “wrapped” - and in our view cannot conceptually be wrapped - in an existing legal entity such as the Wyoming DAO LLC or a Marshall Islands DAO LLC.

Wrapping a DAO effectively means robbing it of its key benefit of being non-hierarchical and widely participatory.

In addition, DAOs have been beleaguered both by the courts but also by investors who bought tokens from them:

The courts seem to pierce through a DAO and go after its members/token holders - going as far as serving notice via the DAO’s community forum on Telegram, and falling back on the default legal analysis of a DAO as an unlimited liability partnership, exposing DAO token holders to joint and several liability for the actions of the DAO.

Investors, including leading VCs, woke up in the middle of the night about the potential reputational risk from having bought tokens in DAOs at the height of the (last) crypto bull market, without clarity about their rights as investors and how the DAO would pay tax, etc., promoting entities such as U.S. Unincorporated Nonprofit Associations (“UNAs”) as wrappers.2

As a result as the above doubts about DAOs, they seem to have fallen out of favor.

The birth of bottom-up companies

However, it is our view that, as was the case with Limited Liability Companies in the U.S., which first gained recognition only in 1977 (by way of a Wyoming law written at the behest of a sole beneficiary, the Hamilton Brothers Oil Company)3, bottom-up demand from a whole community of builders will result in the eventual recognition of a new, fully digital company with legal persona and limited liability, with bylaws written as code and with blockchain itself as its jurisdiction.

In addition, we believe (1) that such DAO-like onchain entity, without the need for any form of legal anchor in a state, has been a validly constituted company throughout - i.e. since Bitcoin as the first DAC - and (2) that its limited liability, as with the Dutch joint stock company of the early 17th century and the Series LLC in the U.S., can be a matter of private contact between all participants.

In what follows we examine these two claims more closely.

International private law to the rescue

Our thesis is that the recognition of an onchain entity as a company sui genesis with limited liability is achievable if we rely on international private law and the freedom to contract.

International private law, which is the body of law that fills the gaps when different jurisdictions are involved (hence “international”), has broadly settled on a cascading definition of what a “company” is.

First, it asks if a company was validly constituted by pointing to the law of the state under which the company is organized. This test is generally passed when the formal publicity and registration requirements set out in the law according to which it is organized are met or, where such requirements do not exist, if it is correctly organized according to that same law.

Second, absent proof of valid constitution, international private law looks for where the company is actually administered. This is typically the place where the fundamental decisions are made and where the company’s operational management is usually located, based on indicators such as the place where the company’s directors meet, the place where the general assemblies are held, the administrative centre where the accounts are kept, and the place where the company’s clients are residing. If the operations of the company are managed from a number of countries, the place where the head office is located, i.e. where the company’s headquarters are, is decisive.

International private law also introduced an escape valve by generally giving a company that seemingly has no valid constitution nor a locus for its administration the benefit of the doubt: in order to protect the interests of third parties who rely on the appearance that a company has legal existence, it tends to automatically recognize foreign entities (the favor recognitionis principle), meaning foreign entities are generally ipso jure recognized.

Onchain organizations are by their nature “international” in the above sense of the word, by virtue of living on decentralized ledgers which assumedly have participating nodes or validators in at least two or more jurisdictions. As a result, international private law has something to say about them.

On the face of it, DAOs would not pass the first test as they are not “validly constituted” given they haven’t explicitly anchored themselves in a legacy jurisdiction.

However, in our analysis it is just a matter of time before blockchains themselves gain recognition as a jurisdiction for onchain companies.

We base this claim on an extrapolation of the existing legal definition used in international private law of what is a “state” and “law”, which in our analysis includes the blockchain and code upon which onchain entities chose to organize themselves.

Onchain entities are organizing themselves such that they do not need to rely on a central government to provide them with the legal framework for their operations and the protections they seek: The fact that they have chosen to rely solely on the technology itself and accept that “code is law”4 does not make them an outlaw, but rather confirms their choice of code as the law governing their company or their lex societatis

Such lex societatis, the laws companies choose to organize themselves and their assets, is a recognized legal principle. In the same way one can choose to organize one’s company under the laws of say Delaware, one has the choice to freely submit oneself to one’s own digital jurisdictional order on blockchain.

On the basis that companies are legal fictions consisting essentially of a bundle of contracts, and that smart contracts are recognized as binding contracts written in code rather than analog prose, then (1) code can be the lex societatis of onchain companies, and (2) blockchains are a digital jurisdictions with functional equivalence to state jurisdictions for the valid constitution of onchain companies.

Wannabee companies

Even if the legacy world may not be quite ready yet to accept decentralized ledgers as new jurisdictions and onchain companies therefore fail the “validly constituted” test above, most projects will probably have some “actual center of administration” under the second test, and even if this is not the case, they would still be considered a company thanks to the favor recognitionis principle mentioned above.

This leads to the inevitable conclusion that even anonymous or pseudonymous pure algorithmic protocols, including Bitcoin itself, are “companies” in international private law. Szabo was right calling them DACs rather than DAOs!

But why would DAOs, who if anything try to escape the gravitational pull of legacy jurisdictions, want to be recognized as a company? What is in it for them?

What’s in it for them is the ultimate prize: limited liability. It is much more favorable for even purely algorithmic DAOs to be recognized as companies sui generis than to be out there in legal limbo or worse: being treated as unlimited liability partnerships, in which each of the holders of the protocol’s native token could be held jointly and severally liable.

Recognition as a new type of company, with code as its lex societatis, will allow onchain entities to gain separate personhood and attain limited liability.

Contracted limited liability

To secure such limited liability, the smart contract code that forms the bylaws of an onchain company would contain contractual references as to the status of token holders as benefiting from limited liability, in the same way that e.g. a Series LLC gains its limited liability by contracting with the Master LLC.

Here again, as in our analysis of blockchains as new digital jurisdictions, we fall back on accepted legal practices, in this case the freedom to contract, which we extrapolate via the theory of functional equivalence.

On this basis, we see no reason why onchain companies could not “contract in” limited liability.

A new vehicle for human ingenuity

The end state is a blockchain-native company in its own right, validly constituted on blockchains, with legal personhood and limited liability, without the need to tether itself to an analog jurisdiction. In other words: a digital entity for the digital economy.

In the same way the Dutch joint-stock company mentioned earlier lead to a power-law proliferation of risk taking since the early 17th Century, the 21st Century digital company simply recognizes the new reality of how people associate and coordinate in the new economy: in a decentralized way, without hierarchies and headquarters, with users as stakeholders and co-governors.

The recognition of onchain entities as companies sui generis validly constituted on blockchains as digital jurisdictions is not pie-in-the-sky but follows from a logical extrapolation of established legal principles, adapted for the new realities of how stuff gets built in today’s world.

If we would not believe that onchain protocols built on smart contracts are set to become the new joint-stock companies, with functional equivalence to state-chartered legacy entities, we would not be doing OtoCo.

Our mission is to engineer such new digital company for the digital economy, giving OtoCo users the choice of using our suite of smart contract to turn existing company forms such as LLCs into code, or incorporate and run their companies natively on blockchains as their chosen jurisdiction.

Szabo, Nick (1994). “Smart Contracts”, 1994, available here https://nakamotoinstitute.org/smart-contracts/

https://a16zcryptocms.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/dao-legal-framework-part-1.pdf and https://a16zcryptocms.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/dao-legal-framework-part-2.pdf for easy bedtime reading.

A nice example of regulatory capture: the Hamilton Oil Company got a new law passed and an entire new company structure approved so it could organize its business in the U.S. with the liability and tax advantages it enjoyed in Panama. Hamill, Susan P. (1998). “The Origins Behind the Limited Liability Company". Ohio State Law Journal. 59 (5): 1459–1522.

The idea of “code is law” comes from Lessig, Lawrence (2000). “Code Is Law – On Liberty in Cyberspace”. Harvard Magazine, available at https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2000/01/code-is-law-html.